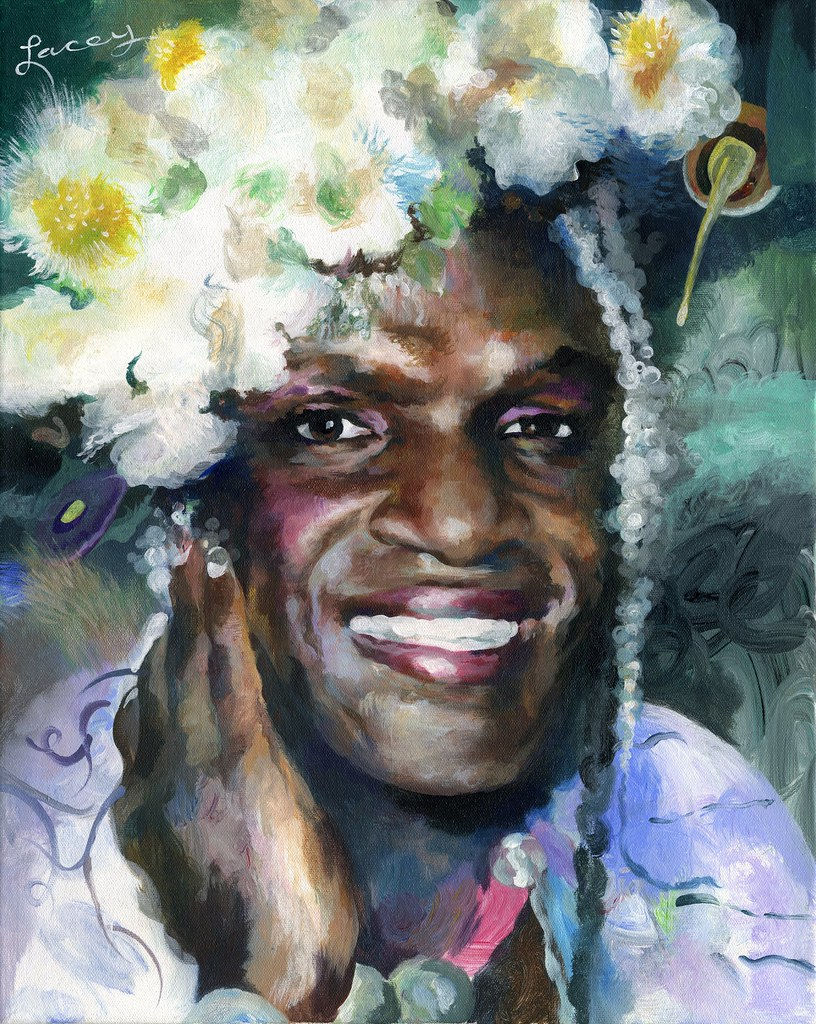

The Patron Saint of Christopher Street: Marsha P. Johnson (1945-1992)

- Thom Jupp

- Jun 21, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 15, 2021

There aren’t many people I consider personal heroes or icons. When we heroize people we often forget to see them as individuals and start to look at them as symbols. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, though, as symbols are extremely powerful. I suppose, for me, heroes are people I aspire to be more like, whose examples ought to be followed. Malcolm X is the first that comes to mind for his fierce activism, clarity of thought, and constant evolution. The Doctor, though fictional, is another for their compassion and creativity, and because I’m a massive nerd. But one who sits above these, however, and one I think about every day, is Marsha P. Johnson.

Born Malcolm Michaels in New Jersey in the summer of 1945, Marsha P. Johnson began wearing dresses at the age of five, a stylish impulse that never went away despite discouragement. With just $15 in her pocket she moved to New York in the early 1960s. This is where the self-identified drag queen Marsha ‘Pay It No Mind’ Johnson - ‘Pay It No Mind’ being her typical response to questions about her gender - was truly born. The New York that Marsha arrived in was a mixed bag when it came to treatment of Queer people. While it was illegal to sell LGBTQ+ people alcohol for some time in the 20th century, and while the Cold War did not provide the most accomodating social atmosphere for Queer people, certain parts of the city attracted LGBTQ+ communities. In these places, such as Christopher Street in the West Village, Queer people found opportunities to live and work as they wanted to in some capacity, forming networks to survive and organize. Marsha did just that.

She performed in drag with the Hot Peaches for a good few decades, a group known for their constant pushing of gender and performance boundaries, while Marsha also developed a unique, authentic look using unconventional and cheap materials to become a gaudy piece of living art. It was this singular style that caught the eye of Andy Warhol, who used Marsha as a model in his Ladies and Gentlemen series in 1975. Marsha also organized Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) with Sylvia Rivera, another Queer rights warrior, to help homeless gay and transgender kids. For a few years in the ‘70s, they even had an apartment called STAR House that acted as a refuge for these kids.

One of the most inspiring aspects of the legend of Marsha P. Johnson is her generosity. Jimmy Camicia, leader of the Hot Peaches, described Marsha’s performances as displaying “the generosity of her spirit” in a way that “was not censored” nor “figured out.” She gave a lot of herself to her co-stars and audience every time she performed, giving her a raw, enchanting energy.

Marsha’s generosity persisted off-stage as well, despite her being practically homeless and often relying on survival sex. Close friend Randy Wicker tells a story of Marsha buying a packet of chocolate chip cookies with her last two dollars and giving them all away “because she had been hungry, had lived on the streets, and she knew that a chocolate chip cookie to a starving queen was a great gift.” Agosto Machado knew her through the ‘60s and ‘70s, and recalls how she “always gave this blessed presence and encouragement to be who you wanted to be,” acting as an icon of liberation for many of her contemporaries. He later compared her to a bodhisattva, and her actions to Jesus and the Feeding of The Five Thousand (if Jesus had crisps instead of loaves and fishes). You can see why she became known as ‘The Patron Saint of Christopher Street’. It is Marsha’s generosity that makes her such an important person to me. Not just her generosity to Queer people in need, but her proud essence that inspired the people around her as it does today. Her compassion persisted throughout her life, and we can all learn from that.

More than what she did, Marsha’s generosity and compassion was who she was. When discussing George Segal’s Gay Liberation sculpture in Christopher Park, Marsha seemed to find the whole concept quite funny. Laughing, she asked: “How many years has it taken for people to realize that we’re all brothers and sisters and human beings in the human race?” This philosophy of siblinghood explains Marsha’s generosity: she helped who she could because, in her words, “we’re all in this rat race together.” This deep empathy and connectedness in Marsha’s worldview was a huge part of her activism, too. On explaining her AIDS awareness and gay liberation activism, Marsha said that “there’s no reason for celebration” when gay people don’t have their rights, because “you never completely have your rights for one person until you all have your rights.”

In July 1992, Marsha’s body was found in the Hudson River near the Christopher Street pier. Her death was ruled a suicide, but the police investigation was tragically, and predictably, inadequate and so her friends never accepted this conclusion. They organized a funeral that combined mourning her death, celebrating her life, and protesting the world that was stacked against them, displaying a complicated mixture of emotions found in any oppressed community. Yet Marsha lives on in many forms. The Marsha P. Johnson Institute, named in her honour, “protects and defends the human rights of BLACK (sic) transgender people” through organizing and community-building. Furthermore, Marsha was the subject of the 2017 Netflix documentary The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson, which follows Victoria Cruz at the Anti-Violence Project as she investigates the circumstances of Marsha’s death.

In a world where transgender women and gender non-conforming people face horrific abuse, violence, and death every year for being who they are, with a vast majority of these people being Black or Latinx, it is crucial to remember Marsha as both an icon of gender-Queer people of colour and a lifelong activist who never stopped fighting for her brothers and sisters. More than that, I believe Marsha’s life has meaning that transcends boundaries of nation, race, class, gender, and sexuality. We can all learn from her perseverance, compassion, and style. I know I’m trying to.

If you’re interested more in Marsha P. Johnson, I recommend watching Pay It No Mind - The Life and Times of Marsha P. Johnson by Michael Kasino on YouTube, and checking out The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson on Netflix.

コメント